By 9pm on 9 May, 2018, the results of the Malaysian general election are just beginning to become clear. My family friend Sham, her two twin daughters and I abandon a shopping trip in Kuala Lumpur once the first results begin to trickle in. We need to be where the action is. On Twitter I learn of a rally being held by supporters of the opposition coalition, Pakatan Harapan (Coalition of Hope). We drive down – the closest car park we can find is a few kilometres from the oval. Sham tells the kids, ‘if anything happens, meet back at the car, all right?’

Several hundred people are on the oval already, but the crowd is quickly building. A pickup truck with young men crowded into the tray streams past with the blue, red and white flag of Pakatan Harapan flying from the back. Everyone is tooting their horns and looking for a car park so they can join the growing rally. Street sellers have set up along the outskirts of the oval and are selling iced Milo drinks and mango juice. Someone nearby is deep-frying bananas and the smell wafts through the air. In the football field there is a massive projector screen set up on a stage, and the Malaysiakini (the country’s largest online news platform) stream is following the seat by seat results.

Pakatan is way ahead now. Each time another seat falls the crowd erupts in spontaneous applause. In the crowds the old chants break out, the chants of the late 1990s and the movement for reform, Reformasi, that started with then Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad sacking his Deputy Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim after Anwar challenged his authority and his handling of the Asian Financial Crisis. The Reformasi movement, which started with such hope and promise, ended in tear gas canisters fired on crowds and long jail sentences for Anwar and others involved in organising the protests.

‘Reformasi, Reformasi, Reformasi!’

Malaysia is a complex multiracial and multi-religious country. The Malays, who are constitutionally bound to be Muslim, make up just over half of the country’s population. Malaysians of Chinese origin make up over 20 percent of the population, with Indian Malaysians like Sham and her family and indigenous groups making up around 10 percent each. Along with neighbour Singapore, Malaysia’s large multiracial population sits in stark contrast to the more ethnically homogenous Thailand to the north, and the more religiously homogenous Indonesia to the south and west; politics, often divided along racial and religious lines, is thus particularly complicated. The constitution, written up by the British, dictates that the Prime Minister must be a Malay, and since independence in 1957 the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) had ruled as the dominant partner in coalition with smaller Chinese and Indian ethnically based parties.

Nobody seriously expected the populist wave sweeping authoritarians to power across the region, from Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines to Narendra Modi in India, to hit Malaysia.

But against the backdrop of the 1998 Kuala Lumpur Commonwealth Games, Anwar Ibrahim tried to turn the country’s racially divided politics on its head. After being sacked as Deputy Prime Minister, he formed the People’s Justice Party (Parti Keadilan Rakyat or PKR) and invited activists and members of all races to join. When Anwar was sentenced to long prison terms for corruption and sodomy (charges he has always denied and maintained were politically motivated), PKR joined with other parties to form an opposition coalition, Pakatan Rakyat (Peoples Coalition), which made significant electoral gains in the 2008 and 2013 general elections, sending shockwaves through the mighty UMNO party apparatus. Despite also making gains at previous polls, on that night in May 2018 almost no one expected this coalition, now reorganised as Pakatan Harapan, to win, to take the capital and seize power at the election.

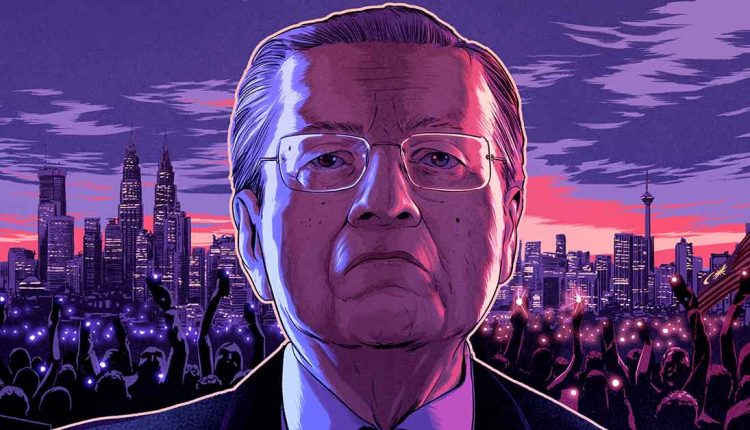

Leading Pakatan was the very man they had originally set about to defeat, Mahathir Mohamad. At 92 years old, Mahathir had come out of retirement to bring down his own successor, Najib Abdul Razak. Najib was mired in one of the biggest political corruption scandals the world had ever seen, with billions in state government funds missing and billions also ending up in his private bank accounts. Mahathir was back, he said, to ‘save Malaysia’ – back to right past wrongs and restore the country’s glory from before the corruption scandal had turned it into a global embarrassment.

Statesman Turned Populist Hero

Despite his past as an iron-fisted dictator, his prior willingness to sack judges he didn’t like, censor and control the press and order police to fire tear gas on and arrest protesters, this time Mahathir promised to be a democratic and conciliatory leader, bringing old enemies into his new coalition with the common cause of ousting UMNO and Najib. Some of them, like PKR Vice-President Tian Chua, were my dad’s old university friends who had spent time in prison simply for politically opposing Mahathir. Even Anwar, whose political feud with Mahathir had dominated Malaysian politics for almost two decades, met and shook hands with Mahathir in a Kuala Lumpur courtroom in September 2016. After the election, Anwar would quickly be granted a royal pardon and released from prison; as part of their coalition agreement the 92-year-old Mahathir would eventually hand over power to Anwar, who was given the title of ‘Prime Minister in waiting’.

On election day, the old statesman turned populist hero seemed relaxed, unfazed by the herculean task ahead of his newly formed Coalition of Hope. But then again, nothing seemed to ever faze Mahathir – the old master always appeared to be 10 steps ahead of his political opponents.

One by one the government seats fall – first in the cities, where the votes come in faster, then the rural villages, the kampungs. Even the Malay villages turn for the first time ever to the opposition.

Doctored images of tanks on the streets of Kuala Lumpur and rumours of a declaration of martial law begin circulating on WhatsApp. Sham’s mother calls, telling her to make sure the kids are home safely and the doors locked. She is old enough to remember the race riots of 1969 and the violence that ensues when the political establishment feels threatened. Sham reassures her not to worry – we were just at the mamak stall for dinner and are heading home now. ‘Are we leaving?’ one of the twins asks. Sham laughs, ‘No, we aren’t going anywhere, not on your life’.

The football field has thousands chanting at fever pitch now. Pakatan is pulling further and further ahead. Foreign media outlets with their cameras and lights set up around the edge of the oval are all calling it – Pakatan had won an upset landslide victory and the 92-year-old Mahathir would become the Prime Minister once again. The oldest leader in the world. The man who ruled for 22 years with the party he had just defeated. For the first time in 61 years, UMNO had been removed from power. For the first time since independence from the British, the government has changed.

On the stroke of midnight, the chanting stops at the football field. Tens of thousands of people turn on their phone’s flashlights and wave them in the air, a symbol Mahathir has embraced at each of his rallies. Together we all sing Negaraku, the national anthem.

As a journalist, I try to keep myself pretty detached from politics, political parties and the hopes and disappointments of the supporters of various leaders. But even I am caught up, overwhelmed by the moment and singing along with everyone else with a full voice swelling with pride in this nation. A small tear is in the corner of my eye. This is a new day, a new dawn. Malaysia Baru. A New Malaysia.

Blow After Blow

Mahathir’s first 20 months in power was marked by disappointment, U-turns and backflips. A website called Harapan Tracker kept count of the government’s performance in following through on the promises laid out in their manifesto. After 685 days in office, of the 556 promises Pakatan had made to the country before the election, only 26 had been achieved. 122 were in progress and almost 400 hadn’t even been started on yet. For everyday Malaysians this marked a series of frustrations; they had voted for change, but still the cost of living continued to rise and wages stagnated. Much needed foreign investors, whom Mahathir had promised would come roaring back into the economy after the election, instead stood idle on the side lines watching to see whether economic reforms would really be carried out. In a series of closely watched by-elections, voters made their feelings heard, delivering Pakatan blow after blow and handing prized seats back to the regrouping UMNO under the leadership of Najib’s former deputy, Zahid Hamidi. A series of by-election defeats in late 2019 created a sense of despair among some in Mahathir’s government, who began ways to change the course of the administration.

Chinese Malaysians have long been the bogeyman of Malaysian politics – anxiety over Beijing’s influence often a cover for good old-fashioned racist dog-whistling. But Mahathir had ignored that and drawn in many members of the Democratic Action Party (DAP) into his cabinet, even appointing Lim Guan Eng, a top DAP politician to the powerful post of Minister of Finance. The predominantly Chinese political party (at times nicknamed the Developers Action Party for their pro-business policies) was an easy target for the now UMNO opposition who had teamed up with the conservative Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS), to form a united front of Malay-Muslim parties trying to bring down Mahathir’s government.

The plotters inside Mahathir’s government saw Pakatan’s close embrace of DAP as the reason for the by-election defeats and began hatching a plan to kick the party out of the governing coalition. There were two main figures leading the plot, one being Muhyiddin Yassin, Mahathir’s second in charge, the other being Azmin Ali, an ambitious politician from Anwar’s PKR party who had his own eyes on the top job and wasn’t afraid to undermine Anwar to get it. For months tensions between Azmin and Anwar has simmered just below boiling point and rumours of a party split had been flying. It all came to a head in February 2020 at the luxurious Sheraton Hotel.

Sheraton Move

For some reason, Malaysian politicians love to make their moves at 5-star hotels. In a series of events the Malaysian media has dubbed Langkah Sheraton, or the ‘Sheraton Move’, Azmin and Muhyiddin met with key leaders from UMNO and PAS at the Sheraton and hatched a plan to form a ‘backdoor government’. UMNO and PAS would join with Muhyiddin’s party along with a faction of Azmin’s supporters from PKR and together they would form a new Malay focused government, kicking out the Chinese dominated DAP and removing Anwar from his anointed post of Prime Minister in waiting. The initial plan was for Mahathir to remain leader of the government, but just switching the component parties which made up his administration.

Mahathir would later claim that he had no idea what his lieutenants were up to; that they had gone rogue. But by now Mahathir was 94, and allies of Anwar had begun pressuring for an exact handover date for when he would give power to Anwar. Mahathir was hesitant and repeatedly said he needed more time to get the country’s still recovering economy back on track. Perhaps Mahathir thought that the threat of a backdoor government and the threat of Anwar being side-lined would be powerful enough to keep Anwar and his allies off his back and give him space to breathe. Perhaps he thought Azmin and Muhyiddin were all hot air, and their plans would never materialise anyway? If so, it was a rare miscalculation for a man that made few political mistakes.

In the days following the Sheraton Move in late February 2020, Malaysian politics exploded. Far too many things happened to accurately summarise them all: the plotters moved to form a new government, but Mahathir refused to play ball with UMNO in particular, seeing as the party included Najib, who was now facing corruption charges in court. So, he quit as Prime Minister, hoping to be reappointed the next day as head of a new national unity government of all political parties not facing charges. But all the parties rebuffed Mahathir’s call for a national unity government, seeing it as a way for Mahathir to simply further entrench his own power and have each minister only beholden to him. In the end, Malaysia’s king appointed Muhyiddin Yassin as the country’s next Prime Minister, with his allies Azmin, UMNO and PAS in tow. UMNO, which had ruled the country for more than six decades was now the largest coalition partner in government again. Sure, Muhyiddin was leading the ship, but with a small number of MPs in the government from his party, he would be beholden to the old guard. The opposition’s control was a blip on the radar, a very brief 20 months, an aberration on the political landscape.

Brutal Game

I first interviewed Mahathir for SBS World News in April 2017. My first impression of him was his wit and the speed at which he answered questions despite his old age. He was charming and had a way of drawing you in with his way of speaking and communicating. At the time he was playing the reluctant leader, the statesman who didn’t want to be prime minister but was drawn into battle to ‘save’ the country. It was easy to get caught up in the moment with him and his narratives, but in retrospect that reluctance was nothing more than a political strategy. The final question I asked was whether or not he, the man who had brought down every single one of his political rivals throughout his many decades in politics, had made a miscalculation, whether Najib would finally be the one politician who had got the better of him. He laughed at the question, but replied firmly: ‘No, Najib will not get the better of me.’

At the age of 92, the wry old man was able to keep his promise and get the better of Najib at the elections. But now he was 94 – perhaps he was fading, perhaps he had finally made a mistake by stepping down as Prime Minister instead of using the power of his office to control the situation. In the backroom shadows of the Sheraton Hotel, Muhyiddin had finally gotten the better of him.

Politics is a brutal game, and in Malaysia, where political leaders regularly find themselves in prison once they lose power, the stakes couldn’t be higher. Mahathir is vowing to fight on, vowing to bring a motion of no confidence against Muhyiddin in the parliament and oust him. But it looks like Muhyiddin has the numbers to hold on until the next election in 2023. By then, who knows if Mahathir will even be around to make another political comeback. He has said he still isn’t ready to retire, but there is a sense that the old man’s time has come and gone, that he had his comeback and he blew it. He had it all – the highest office in the land – but still he wanted more. He was unwilling or unable to set a date to stand down, he was unwilling or unable to let go his grip on power that he held like a sword for decades and that he came back from retirement to seize again.

When people used to ask me when Mahathir Mohamad would hand over power, when he would leave the Prime Minister’s office, I would say that the only way he would ever leave office would be in a coffin. Obviously, I was wrong on the specifics, but the fact remains that no one in Malaysian politics had the power to remove Mahathir but himself. And perhaps it’s more fitting of the man, that instead of being taken out by one of his enemies, he was taken out by himself. Blinded by hubris and ego, unable to even contemplate the idea of letting go of power, he took himself out of the doors of the office thinking the very institution itself couldn’t survive without him. Thinking that the politicians of all stripes would come begging to him to continue serving and that he would be back in the prime minister’s chair in a matter of hours. After dominating the country for so many decades he thought the country couldn’t live without him. But time moves forward, and slowly Malaysia will too. – The Asean Post

Jarni Blakkarly is an Australian journalist of Malaysian heritage. He has lived and worked as a journalist in Malaysia extensively over the last half a decade and is now a reporter for SBS World News based in Melbourne.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of The Capital Post.

Jarni Blakkarly is an Australian journalist of Malaysian heritage. He has lived and worked as a journalist in Malaysia extensively over the last half a decade and is now a reporter for SBS World News based in Melbourne.

Jarni Blakkarly is an Australian journalist of Malaysian heritage. He has lived and worked as a journalist in Malaysia extensively over the last half a decade and is now a reporter for SBS World News based in Melbourne.